The first impression of a mini-retrospective of works on paper by Cleveland artist George Mauersberger at Wolfs gallery in Beachwood is that he’s a master technician, or, perhaps that he’s just a master technician and little more.

But there’s more going on in his nearly hyper-realistic watercolors, pastels, charcoal and pen-and-ink drawings. Yes, they are consistently technically impressive. But importantly, they rise above mere facility to convey a magical sense of appreciation for the prosaic facts of the everyday humdrum world.

Technical mastery is, for Mauersberger, a kind of table stakes, a point of entry in his quest to confront the materiality of the world, the mystery of the existence of things, and the possibility of describing them faithfully in ways that show how the hand and eye can see more than the lens of a camera.

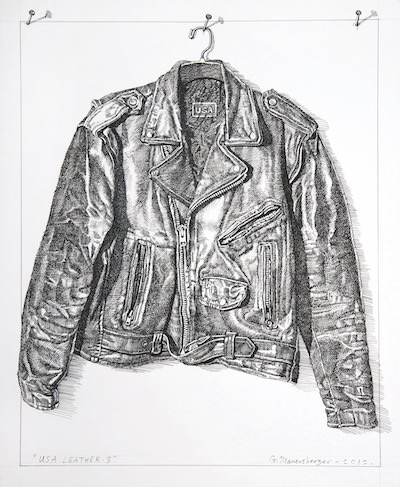

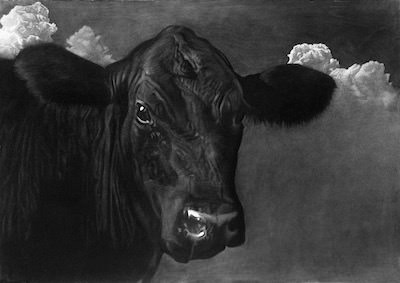

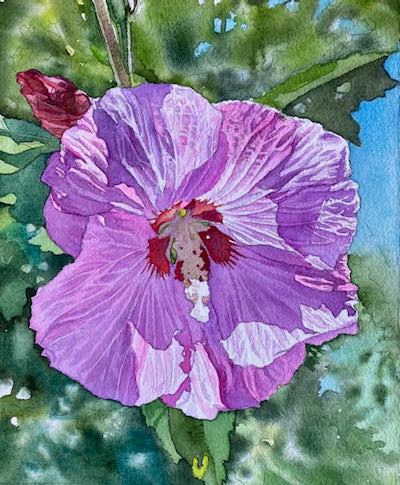

Through his transformative handling of humble materials, Mauersberger is able to convey the ecstatic luminosity of sunlight falling across flower petals, the billowing muscularity of cumulonimbus clouds rising in an inky dark sky, the suppleness of a well-worn black leather jacket, the gleam of mucus on a cow’s nose, and the heavy, dry roughness of concrete cinder blocks.

"USA Leather 3,'' 2012 Pen and ink on paper 17 x 14 inches

All of those images and sensations are visible in “The Strange World of George Mauersberger,’’ opening Friday, December 8 with a reception from 5:30 to 8 p.m. and remaining on view through January 27.

With 27 examples spanning three decades, the show surveys the work of the Cleveland State University professor emeritus, who grew up in the Ohio Valley near West Virginia before earning a bachelor of fine arts in drawing at Carnegie Mellon University in 1978 and a master of fine arts in painting at Ohio University in Athens in 1983. He taught at CSU from 1987 to 2019, according to his website.

The show is sublime and earthy, tender and brutal. At times, Mauersberger is not afraid to be awkward, oafish and even grotesque or gross, but always within limits.

A quartet of self-portraits from 1994 and 1995 are hard to look at. All four present the shirtless artist in closeup profile views. A color pastel from 1994 shows the artist leaning forward in a pose of abject defeat with his forehead lying smack on the top of a table like a rock on a hard impenetrable surface. Ouch.

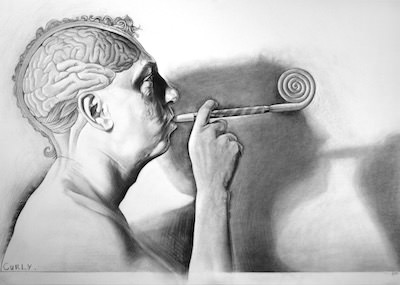

In “Prick,’’ a 1994 charcoal drawing, Mauersberger shouts into the handset of a telephone held to his mouth. In “Curly,’’ a 1995 charcoal drawing, he shows himself again in profile, tooting on a party blower whose curling tip echoes the whorls in his brain, which is revealed magically in the image as if half of his skull had been removed.

"Curly," 1995 Charcoal on paper 30 x 43 inches

Brutality is also present in “Nerf,’’ 1995, a colorful pastel depicting a stack of concrete blocks piled on harshly green grass next to a pink-orange foam ball. The drawing conveys the crushing weight and abrasive texture of the concrete next to the puffy lightness of the ball, while also contrasting awful green of the grass with the near complementary hue of the ball. It’s a nails-on-the-blackboard moment.

Acidic and bilious color harmonies are also part of “Webb,’’ 1992, an image of a folding yellow lawn chair set on bright, sour-green grass in front of a harshly red, one-story clapboard house.

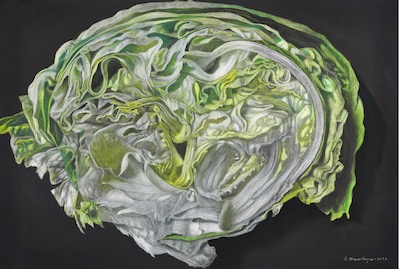

In a trio of drawings that form a kind of visual bacon lettuce and tomato sandwich, a sliced-open head of iceberg lettuce in a 2021 image is like half of a human brain — perhaps a reference to the artist’s 1995 self-portrait with his brain exposed.

"Iceberg," 2021, Pastel on black paper 30 x 44 inches

The monumental beefsteak tomato in a 2020 drawing crowds its tight frame like the monstrous apple in Rene Magritte’s 1952 painting, “The Listening Room.” And the three parallel slices of bacon in a 2022 drawing, glistening with fat, are not just yummy strips of gateway meat, but very obviously pieces of flesh from a warm-blooded creature, slaughtered to satisfy human hungers. Viewed quickly as if it were on display in a breakfast restaurant, the bacon drawing is almost humorous. Looked at more closely, it’s enough to turn anyone into a vegetarian.

Mauersberger’s visual description of things suggest not only that they’re worthy of attention, but that they emanate a heightened significance as Ur-examples of their type.

The cow depicted in a close-up view of its head isolated against an empty sky and distant white clouds in the 2003 charcoal drawing, “Brownie,’’ is not just a particular animal, but all cows that ever lived.

"Brownie,'' 2003, Charcoal on white paper 42 x 60 inches

The up-thrusting cloud in two 2010 versions of “San Carlos Cloud,” one in white pastel on black paper and the other in charcoal on white paper, is cosmic and explosive — like a nuclear blast. The radiant Rose of Sharon blossoms in a pair of 2023 watercolors radiate an almost religious sense of importance.

It’s easy to describe Mauersberger as part of the contemporary tradition of photorealism, and he does indeed use photos as a starting point.

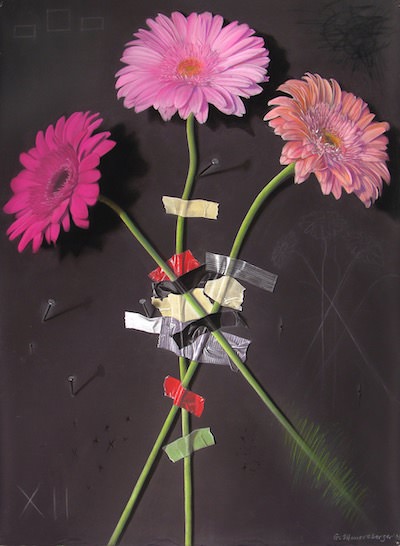

It’s also easy to see Mauersberger as part of the American tradition of trompe l’oeil painting, originating in the 19th century with artists including William Michael Harnett and John Frederick Peto. Like them, Mauersberger often portrays objects seen up close in shallow spaces, pressed up close to the picture plane. He also uses the trompe-l’oeil device of portraying objects fastened to a wall, as in floral still lifes from 2006 and 2023.

"Wallflower 12,'' 2005 Pastel on black paper 53 x 40 inches

But those descriptions don’t fully capture what Mauersberger is seeking. The sense of sublime universality that pervades some of his works echoes tendencies described by art historian Robert Rosenblum in his classic 1975 book, “Modern Painting and the Northern Romantic Tradition.”

Rosenblum identified the tendency of artists ranging from Vincent van Gogh to Ferdinand Hodler, Piet Mondrian and Paul Klee to treat isolated objects such as a tree or a flower or a mountain as emblems of cosmic significance by centering and isolating their subjects.

"Rose of Sharon 1,'' 2023 watercolor on paper 10.5 x 8.5 inches,

That sense of romance and awe sets Mauersberger apart from other contemporary Ohio realists working in a similar vein, including Lowell Toldstedt of Columbus, known for his razor sharp drawings of candy in crinkly wrappers, and Charles Kanwischer of Toledo, known for his astonishing pencil drawings of construction equipment, torn earth and battered wood frame houses.

Kanwischer and Tolstedt are intimists, working on small scale to communicate elevated perceptions of reality with stunning precision.

Mauersberger prefers larger formats, giving his hand room to move. His technique incorporates a certain softness of touch through which he’s able to suggest precision without looking mechanical. When he resorts to razor sharpness, as in the glistening mucus on the nose of the cow in “Brownie,” he does so by carefully marshaling hard-edged accents, using them only on carefully selected occasions.

What’s true for Tolstedt, Kanwischer and Mauersberger is that the realism of all three is based on entering a zone of consistency in their attack that gives their works an impressive overall unity. There are no weak moments, no lapses in attention or focus. Their work is a high-wire demonstration of skill, but with a purpose in each case.

For Mauersberger, who’s receiving attention now at Wolfs, what that means is that the viewer is admitted to that calm, attentive way of seeing and appreciating that which might otherwise be overlooked.

Mauersberger’s drawings — beyond their occasional weirdness — are a wake-up call. Look, they say, there’s some pretty amazing stuff, all around us, every day. Take a moment and pay attention. You might be surprised at what you see.

What’s up: “The Strange World of George Mauersberger.’’

Venue: Wolfs gallery.

Where: 23645 Mercantile Road, Beachwood, Ohio

When: December 8, 2023 – January 27, 2023

Admission: Free. Call 216 721 6945 or go to wolfsgallery.com

George Mauersberger works on paper, on view at Wolfs, mix tenderness and brutality