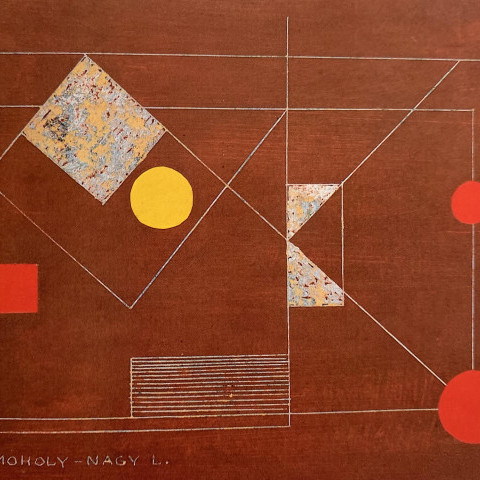

Painter, photographer, philosopher of new aesthetics, filmmaker, builder of light-space machines, and teacher, Moholy-Nagy was born in Hungary. "A prolific writer, as well as one of the most fertile experimental artists of his time, he believed that art offered a way to reorder society after the traumatic years of World War I, and he looked especially to technology to pave the way."

Early paintings by Moholy-Nagy reflected his interest in German Expressionist painting. In the early 1920s, he met Kurt Schwitters and Paul Klee, and explored Dadaism. It was his contact with Russian Constructivism, though, that fueled both the style his art would take and his ideas about art's role as a vehicle for social change. He believed that since art is rooted in society, the artist had a responsibility to address social issues. "He saw the artist as a visionary---one who would provide the forms and ideas necessary for the understanding of future societies."

Moholy-Nagy served as an artillery officer during World War I. In 1918, he received a law degree from the University of Budapest and four years later met Bauhaus founder, Walter Gropius. Gropius was impressed with the young Hungarian's art and his progressive ideas about its potential for improving society. In 1923 Gropius invited Moholy-Nagy to replace Johannes Itten, who had resigned as director of the Vorkurs in 1923.

He wrote the text on Bauhaus photography, "Painting, Photography, Motion Pictures" (1925), which established his reputation. In order to describe his own works, he invented the term "photo sculpture," explaining that "[My works] are composed of different photographs, a...method for testing simultaneous illustration, compromising penetration of the visual and the humor of the word. Yet, they can tell stories at the same time, be concrete, truer to life than life itself."

In 1928, both Moholy-Nagy and Gropius resigned due to increasing political pressure from outside. Moholy-Nagy moved to Berlin, where he did stage design for the State Opera, the Piscator Theater, and experimented with photography, film, and innovative graphic design. He did complete two documentary films in the late 1920s, and in 1930 shot "Lichtspiel, schwartz-weiss-grau," ("Light-play, black-white-grey"), focusing on the play of shade, light, and rhythm.

He spent 1934 doing advanced work with color film and photography in Amsterdam. The following year, he moved to London, where, in addition to making films, he published three volumes of documentary photographs. In 1935, he began making light-space modulators---three dimensional "paintings" on transparent plastics, in which moving light sources cast changing shadows on etched and colored surfaces.

In 1937 he came to the United States to lead the New Bauhaus in Chicago, an experimental school in art and design. When Moholy-Nagy accepted the directorship of the New Bauhaus, he was well known in the United States. By that time exhibitions of his work had been held at various New York museums, the English language edition of his book, "The New Vision," appeared in 1930, and through the various articles he had published in Cahiers d'Art, he was established. Although the New Bauhaus failed for lack of financial support, in January 1939 he opened the School of Design (later called the Institute of Design).

At first the School of Design experienced financial difficulties, but became affiliated with Illinois Institute of Technology, which helped stabilize it. Moholy-Nagy remained as head of his School until his death in 1946 from leukemia. Ironically, that was the year that returning servicemen on the G.I. bill finally brought economic stability to the institution.

In 1939, Ilya Bolotowsky invited Moholy-Nagy to join the American Abstract Artists, and he accepted with pleasure. Although he was unable to attend meetings or actively participate in the group's activities, Moholy-Nagy exhibited annually and contributed a lengthy essay entitled "Space-Time Problems in Art" to the 1946 Yearbook. When he accepted membership, though, he asked to be considered a painter and sculptor, rather than an architect of ideas, and generally showed paintings in the group's exhibitions.

But his death at 51 cut off the stream of his work, but he continues to influence generations of artists.

Source:

Virginia M. Mecklenburg. "The Patricia and Phillip Frost Collection: American Abstraction, 1930-1945" (Washington, DC: National Museum of American Art and Smithsonian Institution Press, 1989), pp. 133-135. Copyright 1989 Smithsonian Institution.

askart.com