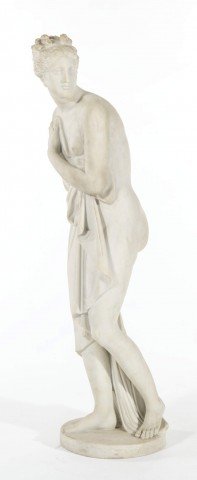

Antonio Canova is considered the greatest Neoclassical sculptor of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Along with the painter Jacques Louis David, he was credited with ushering in a new aesthetic of clear, regularized form and calm repose inspired by classical antiquities. He was also renowned for his carving abilities and the refinement of his marble surfaces, which seemed as supple as real flesh.

Canova was born in northern Italy in the small town of Possagno in 1757 to a family of sculptors and stonecutters, including his grandfather, Pasino Canova, and his father, Pietro. Nineteenth-century biographies of the artist, in a tradition dating back to the Renaissance, suggest Canova’s artistic talent revealed itself at an early age when, as a young child, he carved a lion made out of butter at a dinner party. Although this has been dismissed by scholars as apocryphal, by the age of fourteen, he was apprenticed to the sculptor Giuseppe Bernardi, who was based first in Pagnano, near Asolo, then Venice. After Bernardi’s death in 1774, Canova entered the studio of Bernardi’s nephew, Giovanni Ferrari. In Venice, Canova was heavily influenced by casts of ancient works that he saw, particularly those in the collection of Filippo Farsetti, for whom he completed his first independent work, Two Baskets of Fruit (1774; Museo Correr, Venice). Larger, freestanding figural works followed, including Eurydice and Orpheus, completed for Senator Giovanni Falier in 1775–77 (Museo Correr), and Daedalus and Icarus, 1778–79 (Museo Correr), for Procurator Pietro Pisani.

In 1779–80, Canova made the Grand Tour of Italy, where he saw the great collections of art in Bologna, Florence, Rome, and Naples, an experience he recorded in a travel diary. In 1781, he established his own studio in Rome, which had a thriving cultural and arts scene. Although Canova’s early works revealed the influence of Baroque theatrics in their dramatic subjects, agonized expressions, and twisting forms, in Rome he was influenced by antiquarians, archaeologists, and patrons who promoted a more restrained aesthetic. Theseus and the Minotaur (1782; Victoria and Albert Museum, London), his first major work in this new style, heralded the beginning of a Neoclassical aesthetic and established his reputation as one of the finest sculptors in Europe.

Throughout the 1780s and 1790s, Canova’s reputation continued to grow. He completed commissions in a wide variety of genres: funerary monuments, such as the papal monuments for Clement XIII (1783–92) and Clement XIV (1783–87) (49.116.78), religious subjects, portraits, and mythological deities and heroes inspired by classical antiquity. These latter works reaffirmed his reputation as the leading sculptor of the age. Triumphant Perseus, for instance, was clearly modeled on the Vatican’s Apollo Belvedere (49.97.114), a sculpture that was heralded as a highlight of the papal collection. When Canova’s sculpture was purchased by Pope Pius VII in 1801, it became the first modern work of art to enter the Vatican Collections. The next year, in recognition of Canova’s stature, Pius VII designated the artist Inspector General of the Fine Arts of the Papal States, a post that gave him authority over the Vatican museums and the export of works of art from Rome.

Despite the political turbulence of the period, including the French invasions of Italy and the establishment of the Napoleonic empire, Canova successfully continued to work for a wide range of patrons. These included Napoleon and the Bonaparte family, and his Bust of Napoleon (2015.489) was one of the most widely regarded and reproduced portraits of the emperor. Yet despite his acceptance of these commissions, Canova remained in Pope Pius VII’s favor as well; when Napoleon was deposed in 1815, it was Canova whom the Pope sent as a diplomatic attaché to Paris on behalf of the Papal States.

After the French Empire collapsed in 1815, travel and trade resumed in full force across the continent. The last seven years of Canova’s life were dominated by commissions from British patrons, who were drawn to the artist’s sinuous figures (1970.1), and by the design and construction of a church in his hometown of Possagno. The Tempio, as it is known, allowed Canova to showcase his skills not just as a sculptor, but also as a painter and architect. A cross between the Roman Pantheon and Athenian Parthenon, the church brought together classical architectural features in the celebration of Christ. Canova was also responsible for the design of the sculptural metopes on the exterior; unfortunately, he died in 1822 before those works were completed.

At his death, commemorations were held in Rome, Venice, and Possagno, and he was widely mourned and honored across Europe. The degree of his fame can be measured by the treatment of his corpse, as if it were a saintly relic. Although his body was entombed in the Tempio in Possagno, his hand was preserved at the Accademia di Belle Arti, Venice, and his heart placed in a tomb built by Neoclassical sculptors based on his own design in Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari (67.219.1).

Canova’s Studio and Posthumous Reputation

The degree of Canova’s fame and the breadth of his sculptural production can also be measured by the popularity of his studio in Rome, which became a “must-see” tourist destination. He had a large workshop with many assistants, common practice for sculptors who had many commissions, due to the lengthy and grueling process of working in marble. Canova was frequently present, modeling large clay models or carving marble, and travelers on the Grand Tour made it a regular stop in the hopes of seeing the artist or simply admiring his works. For those visitors who could not afford a Canova sculpture, there was no shortage of tourist souvenirs available in the city; many purchased small cast impressions of intaglios after Canova’s works that were available as sets from local vendors (1992.405.1–.35).

Visitors to the studio were introduced to the full range of Canova’s work, and the studio became a proto-museum of sorts. It also laid bare the many steps of sculptural production. These included the creation of small terracotta bozzetti, large clay models, a variety of plaster casts—both working models and ones after finished works—and, finally, the marble itself. The Metropolitan is fortunate to have one of Canova’s working casts, Cupid and Psyche (05.46), a preparatory model for the second version of the work; it is studded with metal pins, which assistants would have used to transfer the design to a marble block (130.8 C23). Keeping plaster casts like this on hand also allowed Canova and his assistants to make replicas of works for patrons; he could, moreover, continue to make modifications to the casts as his ideas about the work changed. Therefore, although sometimes he produced several versions of a work, he never copied himself directly. The Perseus with the Head of Medusa in the Met’s collection (67.110.1), for instance, was made for the Polish countess Valeria Tarnowski, who had seen Triumphant Perseus in the studio. The Met’s version, however, is not a mere copy of the first; in the second version, Canova grew more daring in his execution of the sculpture and eliminated the marble strut that supports Perseus’ outstretched arm in the Vatican’s version.

In the years following his death, Canova’s fame was so great that works that remained in his studio were completed and sent off to eager patrons (2003.21.2; 2003.21.1). A brisk trade in Canova works was complemented by the reproduction of his more lyrical designs in other decorative arts (26.267.85). A museum in Possagno, the Gipsoteca Canoviana, conceived and constructed by Canova’s half-brother, Giovanni Battista Sartori-Canova, in 1836, was opened in the artist’s memory and features a large collection of working casts that formerly had occupied the studio. Although Canova’s reputation suffered a decline in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it was revived by Italian scholarship in the 1950s, and today he has resumed his place as one of the most important sculptors in the history of art.

Source:

Ferando, Christina. “Antonio Canova (1757–1822).” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–.

http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/nova/hd_nova.htm